McCarthy: big rivers, big glaciers, big mountains

Glaciology Summer School

Every second year, an International Summer School in Glaciology is held in McCarthy (see Map further below). A summer school typically consists of a series of lectures, exercises and field excursions concentrated over a couple of days in a certain location, to give a deep introduction into a specific research field to graduate students. The summer school in McCarthy is unique in many ways: the location is literally thousands of kilometers away from any other University (out of Alaska), the students are simply camping for 10 days in a remote place without running water, and the lectures are held in a cozy block hut. In brief: since the first edition of the McCarthy summer school, this course is definitely a term for young glaciologists and a bunch of applications floods the organizers every time the course is announced. The summer school is organized by the Glaciers Group at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, where Pascal is doing his Postdoc. That’s why we were invited to join the group for a few days to meet people, attend lectures and join the excursion. Since Pascal plans to conduct research on one of the glaciers close to McCarthy, this was also a good chance to inspect the location in person, not only using maps or GoogleEarth (which is still very helpful anyway).

Our cozy class room in a block hut (left). Our cozy camping ground in McCarthy (right).

Road to McCarthy

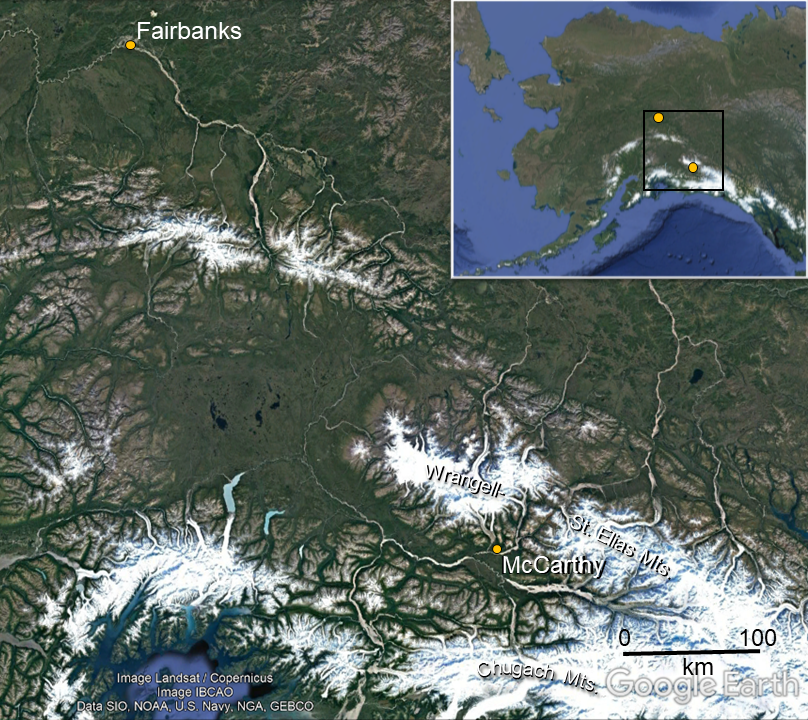

McCarthy, a tiny back-country village with roughly two dozens of inhabitants, lies in the Wrangell-St. Elias Mountains, a mountain range shared by the states of Alaska and Yukon Territory (Canada) and confined by a National Park which is bigger (> 53’000 square kilometers) than the size of Switzerland. The Wrangell-St. Elias Mountains are located southeast of Fairbanks, fairly close to the Pacific coast to the south and the border to Canada to the east. It is about a 9 to11 hour drive (depending on the stops to enjoy the amazing views) of which the last two hours are on a dirt road from Chitina to McCarthy. If we, having just arrived and settled in Alaska 10 days ago, were not fully aware yet of being in a remote, wild and astonishing region of the earth, the last 60 miles on this gravel road entirely engulfed us in the wilderness. We saw a huge river, free to flow without any restriction, a vast flood plain, lots of rabbits and few moose. But, not only. From the car, we saw our first two bears: bear number one, a grizzly running into the woods, and bear number two, a baby black bear quietly crossing the road. In the safety of our car, free from fear, we were able to fully admire these fascinating creatures. In addition we experienced a sequence of heavy rain, sunshine, and dust from the river banks. Chitina River (see further below) is the main tributary of Copper River, which flows into the Gulf of Alaska east of Cordova. The picture helps to understand, that sometimes Copper River is able to transport as much sediments into the Ocean in one single day as does Mississippi during an entire year.

Map of south central Alaska, with Fairbanks in the north and McCarthy within the Wrangell-St. Elias Mountain Range in the south. Map source: GoogleEarth

Chitina River, a river without confines, just before entering Copper River. The river bed is about 900 m wide at this location.

The rise and fall of Kennecott

McCarthy has the spirit of a gold rush village in the middle of nowhere. Wooden cabins, one or two hostels, no asphalt streets, no cars allowed. It seems like McCarthy was frozen for at least half of a century, sort of a ghost town. And so is Kennecott, five miles away and a bit closer to the mountains. McCarthy co-existed with Kennecott, raised and fell with its neighbor village. Kennecott was a mill town, erected in the early 20th century when copper ore was found in huge quantities in the mountains above. The Kennecott Copper Corporation extracted the ore in the mines high up above the village, used gravity to process it to high-grade copper material in the village (see picture below), and finally transported the precious mineral via railroad to the Ocean. The company run the village for about 30 years until 1938, when the copper prices became too low and the business in such a remote place was not economically advantageous anymore. The company hastily abandoned Kennecott. All the buildings where left behind untouched during most of the century. Nowadays tourists can visit Kennecott and its mining infrastructure. The spirit of Kennecott could not be better expressed than by these words from the National Park Service tour guides: “The impressive structures and artifacts that remain represent an ambitious time of exploration, discovery, and technological innovation. They tell stories of westward expansion, World War I politics and economy.” We did a guided three hour-tour and can say it is definitely worth the price of the ticket.

The village of Kennecott with the lost mill building at the top of the houses (left) and the view outside its windows down on the derbis-covered Kennicott Glacier (right).

On the glacier

During our three full days in McCarthy we mainly explored Kennicott Glacier (the village is spelled in a different way, probably due to a mistake). This glacier is quite big, about 293 square kilometers, similar to the size of Canton Schaffhausen in Switzerland or roughly the Altipiano of Asiago in Italy. Walking up more than 40 kilometers from McCarthy, where we camped, to the highest point of the glacier, one faces the impressive southeast-flank of Mount Blackburn, which misses only a flagpole to reach 5000 m a.s.l. More interestingly, especially for Pascal’s work, the entire glacier tongue is covered with debris. Therefore, predicting how the glacier responds to climate change is rather complex. We will talk more about debris-covered glaciers and its implications in coming posts. Together with the Summer School class, we went on a glacier excursion on Root Glacier, a tributary glacier nourishing Kennicott Glacier. This was the first time Anna stepped on a glacier, it was a perfect day out there! Some fellows even took a bath on a glacier lake – on the ice. The water temperature was not much above the melting point, but it doesn’t seem to represent a barrier for crazy glaciologists.

Anna on Root Glacier, a tributary arm of Kennicott Glacier (left) and students preparing for a bath on a melt pond on Root Glacier (right).

We are impressed by the massive dimensions of the landscape and the glacier that we have seen during these days. We can almost not imagine that there are way bigger glaciers just over the ridge towards north or towards south in the Chugach Mountains. We have to adapt to the sizes and distances in Alaska. But maybe we don’t, and we just keep feeling amazed.